The explosive growth of economic inequality over the last fifty years and its impact on education, have led to festering, inchoate resentment and distrust of many Americans. They have been left behind, and they know it. Our democratic institutions are faltering, and our public education outcomes are disturbing. These systems can only be revived by leaders who recognize the dangers of unbridled capitalism and who are unafraid to propose bold action to limit the power of wealth and reinstate the guardrails and safety nets of a social democracy. In responding to this crisis, John Rawls Theory of Justice provides the theoretical framework.

How Unregulated Capitalism is Killing Democracy

In the past months, the election of Zohran Mamdani for mayor of New York City, the Venetian wedding of Jeff Bezos, and the gilding of the White House by the president, present starkly different views of the U.S. economic landscape. The first points to the broad appeal of a message of economic justice, the others to the persistent fascination of Americans with extreme and ostentatious wealth. The passage of Trump’s budget bill makes it clear that the priority of the Republican party is benefitting wealthy donors and corporate interests rather than the “workers” it has pretended to champion.

Since the 2024 election, many voices in the Demcratic party have attempted to assess the causes of their party’s loss. They point to Biden, Harris, poor messaging, failure to address immigration concerns, or to the combined unfortunate effects of COVID, inflation, and two ongoing wars. While all these factors were undoubtedly in play, historical data on income and wealth point to much more long-term and pervasive issues that neither party has adequately addressed.

Democrats contend they are the true party of workers, of the middle class, and of a social safety net. And yes, many of the most devastating policies of the last fifty years have been the doing of Republican administrations. However, the reluctance of the Democratic party to fully prioritize economic justice, and its willingness to compromise with monied interests have failed to avert the crisis in which we now find ourselves. The compound of economic inequity with a declining ability to read and think critically is the volatile mix that breeds resentment and distrust.

In this first article we explore the facts of increasing inequality and its impact on educational outcomes. In articles to follow, we will examine the reasons that unregulated capitalism fails to achieve economic justice. We will look at the meaning of equality as it is expressed in the Declaration of Independence, and how that is being subtly challenged by the social Darwinism of many oligarchs.

Finally, we will revisit John Rawls’ theory of justice as the antithesis of social Darwinism. His theory provides a theoretical framework for the American aspiration to equality, and the foundation for a social democracy.

- HOW INCREASING INEQUALITY HAS IMPACTED CIVIC LITERACY

Over the last ten or fifteen years so many economists and social scientists have highlighted the increasing inequality of American society, that it seems unnecessary to add another voice to the chorus. Nevertheless, to refresh our collective memory, a few of the most startling facts bear repeating.

Economic Inequality in the U.S. has Increased Dramatically in the Last Fifty Years

- Since 1978, CEO compensation in the U.S. has increased 1085% while the typical worker’s compensation has increased 24%.

- In 1965, CEOs were paid about 21 times as much as a typical worker, while in 2023 their pay was about 268 times that of their workers.That’s an average over most companies. In some S&P 500 companies, especially those with many low-wage workers, CEO pay is five hundred to several thousand times that of the median worker.

- The U.S. has the very worst income inequality of the highly developed nations, and among the worst in the world. Two-thirds of all countries – developed and less-developed - are more economically equal than the U.S.

- The lower half of the income spectrum, earning below $80,000 per household, includes households headed by teachers, retail and hospitality workers, social workers, and lower-level managers as well as “blue collar” workers.

-

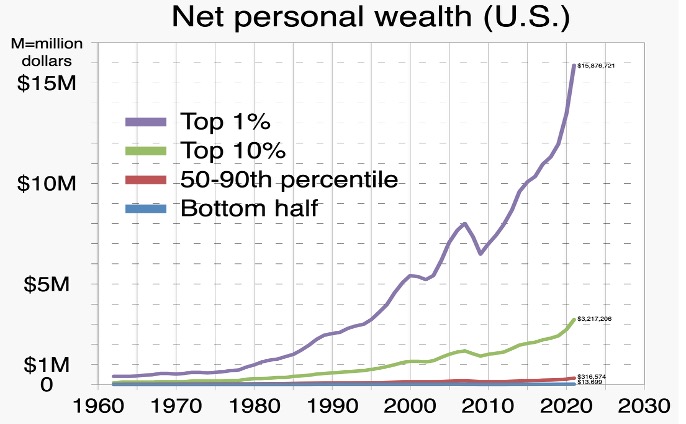

Wealth inequality has increased even more than income inequality since the 1970s. The top 10% now control 67.2% of the wealth of the country, while the bottom 50% of households control just 2.5%.

- The inability to save, buy a home, and create household wealth is aggravated by the fact that real incomes for lower- and middle-class workers have not kept pace with overall income growth.

- While women and minorities have a slightly larger share of the total income of the lower and middle-class workers than they did in 1980, the portion of the pie going to those classes has shrunk. Upper income groups, especially the top .1% to 1%, earn dramatically more (allowing them to save, invest and build wealth) while the bottom half of earners have seen real wages and income increase much more slowly. White, non-college educated males have seen their real wages decrease.

-

It is difficult to overstate the impact of this inequality on our political landscape. The relevance has to do with the festering, ill-defined resentment and distrust of half of the population that expected an equal opportunity to succeed and found the deck stacked against them. Many of them have been deprived of the dignity of regular work by insufficient education, health, or opportunity. They are willing to believe many untruths or half-truths that offer a simple explanation of their plight; immigrants, China, government bureaucracy, and the liberal elite become favorite targets.

The Impact of Inequality on Education and Politics

Income inequality has serious repercussions for equality of opportunity in education, especially in public schools. Despite heroic efforts by many educators, overall U.S. outcomes in reading and mathematics have fallen behind other developed countries, and the achievement gap between students from higher social-economic status (SES) households and those from lower SES homes, which had narrowed very slightly prior to COVID, has now increased again. The factors include both the effect of lower income on individual households and students, and the effect of the structure of our economy on education.

Household Income Inequality Impacts Children’s Outcomes

This effect of household income inequality on educational quality and opportunity is often ignored. Yet, in 2024, about 70% of public-school students were eligible for free or reduced lunch. This seems counter-intuitive, but part of the explanation for this high percentage is that upper or upper-middle income families can send their children to private or parochial schools. It is also the case that a family with more school age children may be more likely to have children in public schools and/or be lower income.

Although the percentage differs by state and district, this means that a majority of public-school students nationwide are economically disadvantaged; they come from households earning less than 185% of the poverty level – or less than $60,000 for a family of four.

A 2022 review of the impact of SES on outcomes from 1961-2001 concluded that:

…. research has consistently shown that children from different families reach different achievement levels and that these family differences are highly correlated with family SES. Coleman et al. (1966), in their seminal study reported in Equality of Educational Opportunity, found parental education, income, and race to be highly correlated with student achievement…Subsequent research into family factors has consistently confirmed these early findings on the role of families.

A 2016 study by Duncan and Murnane on the effects of rising income inequality on educational outcomes indicates that this impact has increased because of the widening household income gap.

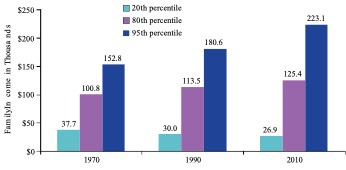

Compared with 1970, the 2010 family income at the 20th percentile of income has fallen by more than 25 percent to about $27,000. In contrast, the incomes of families at the 80th percentile grew by 23 percent, to $125,000, and the incomes of the richest 5 percent of families rose even more. These growing income gaps translated into increased gaps between the academic achievement and educational attainments of children from high- and low- income families.

In the late 1960’s, test scores in the reading of low-income children were lower than their high-income peers by about 80 points on an SAT-type test scale. By the early 2000’s this gap was nearly 125 SAT-type points, or nearly 50% larger. Trends in mathematics skills are similar.

From the 1960s to 2019, the skills of lower income children were improving slowly. Math scores of lower income students increased by about 40 points, and racial differences had diminished. However, the scores of high-income students have increased much more – around 70 points on a similar scale.

Since COVID the scores of low-income students have stagnated or fallen while the scores of high-income students have largely recovered or improved. Thus, the gap between low-income and high-income students has widened even more than in the previous decades.

Household factors that negatively affect educational progress because of income include:

- Less access to high quality childcare/pre-school, and therefore, poor pre-school preparation for kindergarten.

- Fewer resources to buy books, computers, summer camps, private schooling and other educational enrichment expenses

- Longer family work hours to make ends meet, especially in single-parent households, resulting in less quality time interacting with children or helping with schoolwork

- Less exposure to novel environments, whether locally or through travelMore family stress and dysfunction aggravated by low income, poor health, housing relocation, or low employment security.

Structural Economic Effects on Educational Outcomes

-

Heroic efforts have been made to improve educational outcomes of lower-income students through early childhood programs, income supplements to families, charter schools, and various special programs. However, other than the early childhood programs, which have consistently been shown to have a positive effect on outcomes, the results have been negligible or difficult to duplicate. In particular, the supplemental income programs, which usually amount to no more than $1000 to $4000 per year per household have had very little impact, possibly because the amount is too small to really make a difference.

There are a number of impacts on education that are the result of systemic inequality. For instance,

- Residential segregation by income has increased dramatically since 1980, resulting in the economic segregation of schools.

- Low-income children attend schools with mostly low-income classmates. These students have better outcomes when they attend schools with higher income and higher achieving students, and they have poorer outcomes than when they attend schools with mostly low- income peers. A child from a from a poor family is two to four times as likely as a child from an affluent family to have classmates in both elementary and high school with low skills and with behavior problems (Duncan and Murnane, 2011). This sorting matters, because a higher proportion of those with weaker skills and greater behavioral problems has a negative effect on the learning of their classmates.

- Concentration of affordable housing in certain neighborhoods or communities contributes to this economic segregation. Immigrant children who need special help with language, or who may have experienced trauma in their home countries, are often concentrated in these neighborhoods and put extra economic pressure on schools to serve them well.

- For multiple reasons, it is difficult to attract and retain excellent teachers in these economically segregated schools.

- Urban families living in poverty move more frequently, perhaps due to job insecurity or opportunity, or to seek a better living environment. This impacts children’s learning.

- Funding of schools by local districts, rather than nationally, exacerbates the differences between schools in high-income districts and those in low-income districts.

- Compared to other industries requiring a bachelor’s degree, teachers are relatively low-paid and under-appreciated. For instance, the average starting salary for all college graduates in 2025 is projected to be over $68,000, while the average for beginning teachers was under $50,000 in 2024. Attracting the best and brightest to teach is a challenge.

Even more fundamentally, a country that values tax reductions for the highest income and for large corporations over funding for education, health and social services cannot hope to have better educational outcomes. It is not a question of merely throwing money at certain school districts or households. It means changing our economic structures and priorities. There are proven ways in which tax dollars can improve educational outcomes: early childhood education and affordable childcare, higher teacher salaries, better teacher preparation, smaller classrooms, longer school days, and affordable housing spread equitably throughout our cities and counties are a few of those.

In sum, higher income families can send their children to private schools if public schools are not up to par. This can impoverish public schools both financially and in the diversity of achievement and ambition that is modeled to lower income students. Schools in high-poverty districts have a lower tax base and less funding despite greater need, often resulting in lower-paid and less-qualified teachers, larger classes, and fewer exceptional programs. Despite evidence that when low-income students are surrounded by more affluent and ambitious students they do better academically, efforts to provide low-cost housing where there are excellent public schools have been half-hearted. If we want to improve the American public school system, we must reduce economic inequality and remedy the geographic concentration of low-income households.

As Inequality Has Grown, Levels of Literacy and Civic Knowledge Have Fallen

With misinformation and outright falsehoods pervasive in our media and cyberworlds, it is essential that basic education impart the skills of critical reading and thinking. Yet in 2024, 32% of 12th graders did not even read at the “basic” level - 12% more than in 1992. This means that nearly one-third of 12th grade students have not yet mastered fundamental reading skills.

54% of U.S. adults read below 6th grade level while 21% are functionally illiterate. While 74% of U.S. citizens over 65 could pass the U.S. Citizenship test, only 18% of those aged 45 and younger could pass it. Can there be any doubt that this low level of literacy has affected our capacity to be informed citizens, or to understand our Constitution and our civic institutions? This is not a partisan problem. Income inequality begets educational inequality; we all need to be horrified by our failure to achieve a more equitable society, and a better prepared citizenry.

Rosemary Curran Ph.D. is an Author, Educator, Theologian and Urban Planning Professional. She has over 20 years teaching at university and secondary levels and was a Fulbright Scholar in Ethiopia.

#

Stay tuned for Part Two, Can a Capitalist Society Be Equitable, in this Three-part series.